MWDH's History

History:The Story of Ming Wah Dai Ha Starts from Shau Kei Wan

George Wan, Founder of Hide and Seek Tour

Shau Kei Wan (literally “Colander Bay” in Chinese) was named after a bay in the shape of a colander01. After Hong Kong was opened for trade in 1841, Shau Kei Wan became one of the first areas in the Eastern District where industrial and commercial development was beginning to take shape.02

Shau Kei Wan was home to one of the coastal quarries in Hong Kong where large quantities of strong and durable granite were produced to meet the high demand for stone from numerous construction projects in the territory. As a result, hordes of Hakkas, known for their masonry skills, were attracted to the area in search of work and many of them settled in the place where A Kung Ngam Village is today. Tsang Koon Man was the most prominent mason amongst these Hakka immigrants, amassing a huge fortune from his work.03 The private mansion he helped build in Sha Tin is now a Grade I historic building known as Tsang Tai Uk.

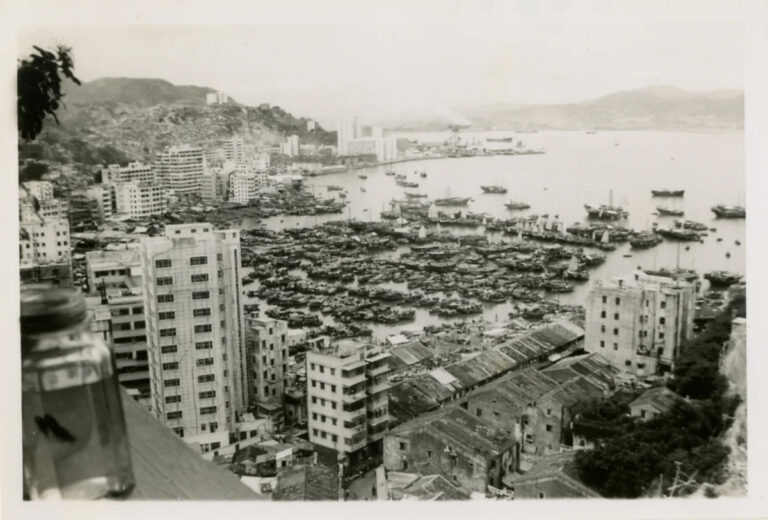

Given its coastal location shielded by mountains, Shau Kei Wan contributed to the growth of the local fishing industry by providing a good shelter for fishermen looking to moor their boats. During the Japanese occupation, the Shau Kei Wan fishing junk alliance was formed, leading to a further increase in catches04. The Shau Kei Wan Wholesale Fish Market at A Kung Ngam Road bore witness to the development of Shau Kei Wan’s fishing industry.

Masons, fishermen and other members of the local community came together to raise funds to build Tin Hau Temple (in 1873)05 and Tam Kung Temple (in 1905)06, in the hope of securing divine blessings and protection at a time when masonry and fishing were considered hard and dangerous work. Shau Kei Wan Main Street East is where the biggest market at the time was located with plenty of shops and restaurants.

In the late 19th century, the British conglomerate Swire broke ground on a sugar refinery at Quarry Bay, followed by the development of Taikoo Dockyard07. The thousands of workers hired for the projects settled near their workplace, resulting in a sharp increase in Shau Kei Wan’s population. Even with a fast-growing community, Shau Kei Wan was still considered a suburban area. There were no buses, and the only means of land transport available was the tram system which started operations in 1904. Not resolved until the 1950s, the problems with public transport in the area were evidenced by a popular quip to the effect that “you would never know when you’ll reach Central when you are stuck in Shau Kei Wan”08.

Shau Kei Wan was also once a military stronghold due to its strategic location commanding the eastern entrance of Victoria Harbour. The Lei Yue Mun Fort was built in 1885 to defend against invading forces and played a huge role in protecting Hong Kong during the war against Japanese invasion.09

Pic 1: Shau Kei Wan in 1961.

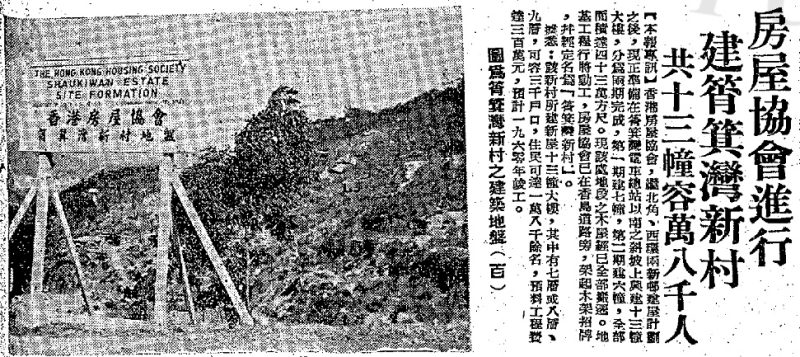

Pic 2: 9 December 1958, The Kung Sheung Daily News, a report on the construction of Shau Kei Wan Sun Chuen.

During the years between the end of the civil war and the founding of the People’s Republic of China, a massive influx of immigrants flooded into Hong Kong from Mainland China. As an acute shortage of housing made it difficult to cope with the sudden increase in population, many low-income residents resorted to building shacks on hillsides in various neighbourhoods, including Shau Kei Wan where a total of 13 villages10 were built. Often densely populated and poorly planned, these squatter areas were a cesspool of unsanitary conditions and a hotbed for fire hazards.

None of the current government agencies at the time were specifically responsible for handling the housing issues, with the Hong Kong Housing Society subsequently established to shoulder the major task of taking the housing challenges head on. In 1947, the Lord Mayor of London donated a sum of 14,000 pounds from its Air Raid Distress Fund to the Hong Kong Social Welfare Council. A member of the Council and the Anglican Bishop of Hong Kong, the Reverend Ronald Hall, proposed to use the donation to establish a public housing provider. The Housing Society was founded in 1948 under his leadership.11

In 1957, the Housing Society was awarded a plot of land in Shau Kei Wan12(where the now demolished Luk Bo Village sat13) by the government. Construction of the first public housing estate in Shau Kei Wan began the following year and the estate was named “Shau Kei Wan Sun Chuen”14 (Pic. 2). Although the project was located on a suburban hillside, residents could easily reach the downtown area given the estate’s proximity to the tram terminus. Later, it was decided to name the new estate “Ming Wah Dai Ha” after one of the Housing Society’s founders, the Reverend Ronald Hall (Chinese name: Ho Ming Wah). The estate was designed by esteemed architect Szeto Wai, who was quoted by the Overseas Chinese Daily News as saying that “the major goal of the building project is to ameliorate the housing shortage faced by low-income individuals and workers who make up a significant part of Shau Kei Wan’s growing population, and to beautify and bring prosperity to the neighbourhood”15. At the same time, A Kung Ngam Road was constructed to make travel easier for residents.

Due to the immense scale of the project, Ming Wah Dai Ha was developed in two phases. Phase One, comprising seven blocks from Block G to Block M, was completed in 1963 while Phase Two, with six blocks from Block A to Block F, was completed in 1965. With a total of 13 blocks, the estate provided about 3,000 flats to accommodate more than 18,000 residents.

Pic 3: 10 February 1966, a plaque unveiling ceremony, officiated by the then Governor Sir David Trench, was held at Ming Wah Dai Ha.

A plaque unveiling ceremony, attended by over 100 distinguished guests, was held on 10 February 1966 (Pic. 3) to commemorate the completion of the project. As the officiating guest, the then Governor Sir David Trench praised Bishop Hall’s contributions and recognised the work of the Housing Society. As a matter of fact, the success of the Housing Society and Ming Wah Dai Ha was largely attributable to Bishop Hall’s foresight and vision. With the estate’s design used as reference for future government-funded housing projects, the Bishop said with pride,“The first batch of resettlement estates built by the government after the Shek Kip Mei fire were based almost entirely on our plans and designs.”16

The flat size allocated was based on the expected number of occupants (35 square feet per person). For newly-released public housing projects, the monthly rent of a flat size 175 square feet designed for a family of five was HKD5917. Even at such low rents, Ming Wah offered a pleasant living environment, with most of the flats equipped with a private kitchen and bathroom. The building also featured public spaces where residents could meet and interact with each other, while enjoying natural ventilation beneficial for their health. The project attracted record numbers of applications, reflecting the common perception of the estate as synonymous with quality living spaces. As reported by the Overseas Chinese Daily News on 14 August 1962, 17,000 applications were received for Phase One, representing an oversubscription of more than 10 times compared with a total of 1,480 flats across seven blocks available for allocation.

In 1976, Block A, not equipped with private bathrooms, was redeveloped. In 2010, elevators were installed in some buildings to help residents get around more easily. In view of the aged building blocks and its deteriorating conditions and to meet the growing housing demand, the Housing Society resolved to redevelop Ming Wah Dai Ha in phases in 2018. The oldest buildings, Blocks K, L and M, were redeveloped into two towers in 2021. The redevelopment of the other blocks is well underway. Works on the redevelopment project is expected to be completed in 2035 to help house over 3,900 families.

註:

1. 饒玖才:《香港的地名與地方歷史(上)-港島與九龍》, Hong Kong, Cosmos Books Ltd., 2003, P.130

2. 郭少棠:《東區風物誌》, Hong Kong, Eastern District Council, 2003, P.20

3. 羅香林:〈香港早期之打石史蹟及其與香港建設之關係〉,《食貨月刊》,New Issue Volume 1 No. 9(1971), P.461

4. 郭少棠:《東區風物誌》, Hong Kong, Eastern District Council, 2003, P.34

5. Chinese Temples Committee:〈筲箕灣天后古廟〉, Chinese Temples Committee Website, 2019, http://www.ctc.org.hk/b5/directcontrol/temple5.asp, accessed on 5 March 2022

6. Chinese Temples Committee:〈筲箕灣譚公廟〉Chinese Temples Committee Website, 2019, http://www.ctc.org.hk/b5/directcontrol/temple7.asp, accessed on 5 March 2022

7. 郭少棠:《東區風物誌》, Hong Kong, Eastern District Council, 2003, P.22-24

8. 饒玖才:《香港的地名與地方歷史(上)-港島與九龍》, Hong Kong, Cosmos Books Ltd., 2003, P.132

9. 郭少棠:《東區風物誌》, Hong Kong, Eastern District Council, 2003, P.77

10. 郭少棠:《東區風物誌》, Hong Kong, Eastern District Council, 2003, P.5

11. 《房協70:創宜居•活社區》, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Housing Society, 2018, P.29

12. Hong Kong Housing Society Annual Report, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Housing Society, 1957, P.15

13. 郭少棠:《東區風物誌》, Hong Kong, Eastern District Council, 2003, P.5

14.〈房屋協會進行建筲箕灣新村,共十三幢容萬八千人〉, The Kung Sheung Evening News, 9 February 1958, P.4

15.〈適應低薪工友需求,筲箕灣廉租屋,地盤工程開始〉, Overseas Chinese Daily News, 3 November 1958, P.10

16.〈房屋協會續建廉租屋,協助解決屋荒,港督備致讚揚〉, The Kung Sheung Daily News, 11 February, 1966, P.4

17. 《情繫明華》, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Housing Society, P.2