MWDH's Architecture History

Architecture: A Commitment to Simplistic and Human-centred Designs

Clara Chan, Co-Founder of Lion Head Culture, Vice-President of Hong Kong Institute of Architectural Conservationists

Background

Back in the 1950s, while the world at large suffered from a shortage of affordable housing, Hong Kong was confronted by a full-blown housing crisis engendered by an influx of immigrants fleeing the civil war in Mainland China. Wooden shacks and tin-sheeted huts were built by tens of thousands of refugees across the hillsides. In 1954, when one eighth of the entire Hong Kong population resided in squatter areas under appalling living conditions and over 350,000 people needed to be relocated, the then governor Alexander Grantham painted a grim picture of the local housing situation in a speech: “If we had unlimited money and unlimited land, the problem would be very much simpler. As it is, we have neither, which makes it that much more difficult.”01

To cope with the overwhelming housing demand, numerous low-cost housing projects were launched in an attempt to provide enough residential units to house, in the fastest and cheapest possible way, those who were financially strapped. Ming Wah Dai Ha, first conceived and planned in 1956, was one such project. The development’s architectural design philosophy predominantly reflected the social needs at the time, and generally in line with the principles of modernism focusing on practicality and function over form—the prevalent design values that informed many works of western architecture at the time.

Ming Wah Dai Ha was designed by W. Szeto & Partners, a renowned and well-established local architectural firm. Szeto Wai, who was relocated to Hong Kong from Shanghai after the war, was a well-versed professional in the fields of structural engineering, civil engineering, public health and electrical engineering. He took part in numerous public institutional building projects in Hong Kong, such as schools, university campuses and town halls02. Despite his engineering background, Szeto’s architectural designs were on par with those produced by his more conventionally trained counterparts03. With his profound knowledge of structural engineering, a hillside building project like Ming Wah Dai Ha was right up Szeto’s alley.

The planning and design of Ming Wah Dai Ha demonstrated its great value as a practical reference for the other housing projects underway in Hong Kong at the time. It underlined the commitment to a human-centred approach to creating habitable spaces for Hong Kong citizens against the immense pressure to keep costs down.04

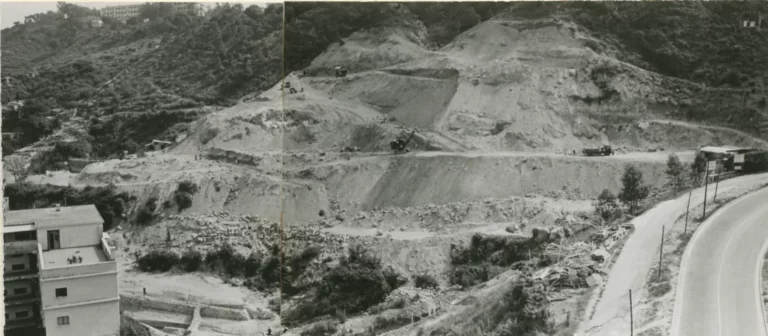

Pic 1:Bare hillsides at the Ming Wah Dai Ha construction site in 1959.

Estate Layout

In 1966, construction of Ming Wah Dai Ha, situated on a hillside in Shau Kei Wan, was officially completed. The estate comprised 13 blocks of low-cost housing oriented towards north along A Kung Ngam Road. With a different design from H-shaped Block A looking out to the sea and the cruciform structure of Block G, the other 11 blocks were 8- to 10-storey rectangular buildings. The estate occupied a total site area of 37,000 square metres, the size of five to six football pitches combined, making it the largest housing project undertaken by the Housing Society at that time.

One of the features of Ming Wah Dai Ha is its hillside location. The early photo (Pic 1) of the building site shows a rocky slope as A Kung Ngam Road had not yet been built then. Planning for the project began in 1957. After inspecting the site, Szeto Wai pointed to the incredibly difficult if not impossible task of hillside construction. According to the Housing Society’s annual reports, construction was delayed multiple times since rocks on the site were harder than expected and the ground was difficult to level. While hillside buildings abound nowadays, they posed a huge technological challenge to builders half a century ago, which is the reason why most buildings at the time were sited on seaside flatlands. However, to cope with the tremendous population growth, government officials had no alternative but to start developing public housing on hilly terrains. Between the 1950s and the 1960s, many hillside public housing estates, such as Yue Kwong Chuen and Cho Yiu Chuen, were completed. Hillside construction became so commonplace that The Hong Kong and Far East Builder published an article in 1959 detailing the technology and methods employed in such projects.

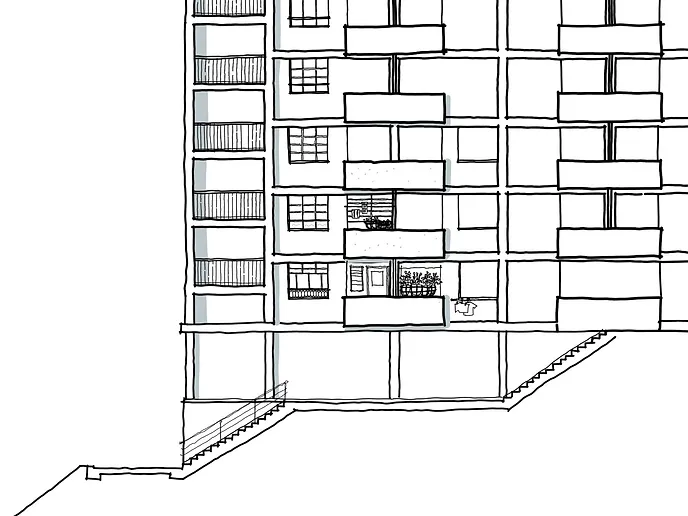

In the end, Szeto Wai opted not to level the whole hillside, but instead shaped the site into extensive terraced fields where buildings were constructed (Pic 2). The design provided each rectangular building with three exits on different levels, leading to the top, the side and the foot of the hill. Take Block J as an example, an exit was provided on the third floor leading to A Kung Ngam Road, while another exit was located on the first floor leading to the tram terminus at the foot of the hill.

Situated on terraced hillsides and sandwiched between the hills and the sea, Ming Wah Dai Ha boasts a quiet and green environment. With the local geographical features in mind, architects worked tirelessly on the layout of the estate to build not just as many residential units as possible to house families, but also ample public spaces to help create a healthy living environment and a better neighbourhood. For instance, each block featured a covered playground on the ground level.05 The vast public spaces between two blocks were blessed with unrestricted views and natural ventilation06, reflecting the Housing Society’s planning principles for public housing estates. Citing a quote from the Housing Society’s annual report: “In spite of the demand for more housing the Society must keep to reasonable standards of density and not be forced into cramming more families on a site than it honestly feels it can manage successfully. Car parks should not replace children’s playgrounds but by more skillful planning both must be provided. Adequate open spaces and gardens are more important than ever in planning estates with multi-storey buildings and our estates can be examples of how a balanced plan can be produced.”07

Early plans of Ming Wah Dai Ha did not provide retail stores due to its proximity to Shau Kei Wan Market; only schools and community service facilities were planned. Until the first intake in 1962, four residential units were converted to stores, selling groceries and providing laundry services.

Pic 2: Many of the buildings at Ming Wah Dai Ha were constructed on terraced hillsides due to the difficult terrain.

Interior Structure and Spaces

In the early stages of the estate’s development, Szeto Wai estimated that the site could accommodate approximately 2,500 families. However, when the estate was completed in 1966, the 13 buildings could actually offer a total of 3,031 residential units, about one fifth more than originally planned. Despite the limited resources available and the need to house nearly 10,000 residents, the interior spaces did not feel cramped, thanks to Szeto’s simple yet intelligent design. Many of the first residents were impressed by the buildings’ ventilation and lighting.08

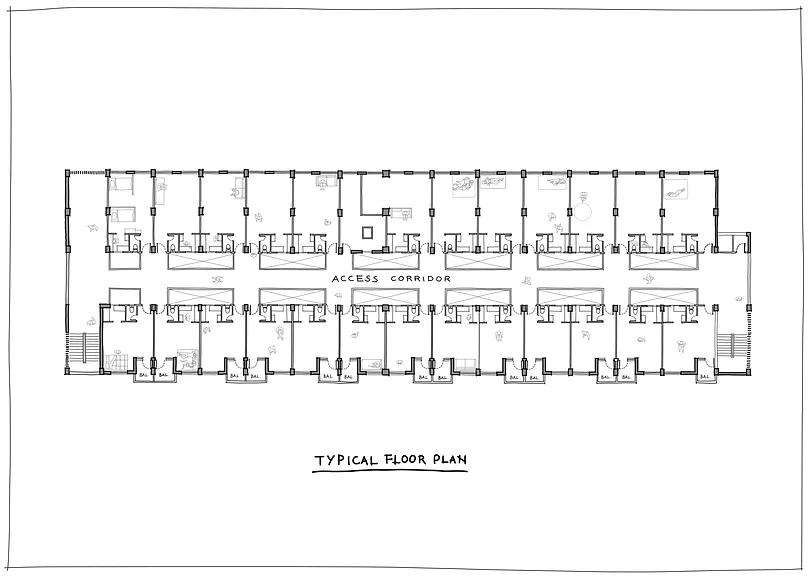

The 13 blocks mostly featured a rectangular design with a skyway-like corridor running through each floor and a roofed and well-ventilated public area at either end of the corridor. The access corridor was lined with a row of residential units on either side. Natural light and fresh air were brought into each building09, helping to strengthen neighbour relations by creating a comfortable atmosphere for residents to interact.10

Pic 3: Ming Wah Dai Ha features a central corridor design, on both ends of the corridor are public spaces shared by residents.

Pic 4: A skyway-like corridor is found on each floor; a roofed and well-ventilated public area is located at both ends of the corridor.

With sizes ranging from 13 to 53 square metres to cater to the needs of families of various sizes, the residential units at Ming Wah Dai Ha came with a private toilet and kitchen. Regardless of the flat size, the basic layout remained consistent. For example, ventilation windows in the kitchen and the toilet always faced the impluvium (air well) located above the central corridor, making it possible for living rooms and bedrooms to have big windows or balconies11. According to Szeto Wai’s plan, 40% of the units came without a balcony12, given the need to lower rental rates and provide more space to house low-income families. To cater to the laundry needs of those residents without a balcony, a space dedicated to clothes drying was set up on every floor.

Such was a prevalent design feature of Ming Wah Dai Ha, with similar methods employed to reduce costs and hence rental rates. Of the 13 buildings, Block A was designed for low-income civil servants and was the only block without private toilets and kitchens. The communal kitchen and bathroom layout was designed to reduce costs. However, soon after the first residents moved in, many Block A residents applied for the transfer of units as they would not mind paying a slightly higher rent for the benefit of a self-contained unit with a private bathroom and kitchen. In response to the demand at that time, Block A was demolished and rebuilt in 1972. Moreover, as a further cost-cutting measure, none of the buildings were equipped with lifts, except for Block G, which was planned to be occupied by higher-income families.

While the buildings at Ming Wah Dai Ha might not look attractive, the design plan attested to Szeto Wai’s caring and thoughtful approach to creating economical and yet human-centred living spaces for residents.

(1) “The Governor’s Pre-budget Address”, Hong Kong and Far East Builder, vol.10 no.5, 1954.

(2) University of Hong Kong: 90th Congregation Citation, HKU website, 1975, https://www4.hku.hk/hongrads/tc/citations/c-b-e-b-sc-ceng-f-i-c-e-f-i-s-tructe-f-a-s-c-e-m-i-m-eche-wai-szeto-the-hon-szeto-wai, accessed on 6 March 2022.

Chinese University of Hong Kong: 20th Conferment of Honorary Degree of Doctor of Law, CUHK website, 30 November 1978, https://cong.cpr.cuhk.edu.hk/uploads/hongrads/380_zh_tw.pdf, accessed on 6 March 2022.

(3) 黎雋維:〈建築師司徒惠的工程結構美學〉, Apple Daily, 2 May 2021.

(4) Hong Kong Housing Society Annual Report 1961, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Housing Society, 1961.

(5) Walter Koditek, Hong Kong Modern Architecture of the 1950s-1970s, 2022: Apsara Books.

(6) Ming Wah Dai Ha, Docomomo HK, https://docomomo.hk/zh/project/ming-wah-dai-ha/, accessed on 6 March 2022.

(7) Hong Kong Housing Society Annual Report 1961, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Housing Society, 1961.

(8) Hong Kong Housing Society Annual Report 1962, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Housing Society, 1962.

(9) Hong Kong Housing Society Annual Report 1958, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Housing Society, 1958.

(10) Ming Wah Dai Ha, Docomomo HK, https://docomomo.hk/zh/project/ming-wah-dai-ha/, accessed on 6 March 2022.

(11) Hong Kong Housing Society Annual Report 1961, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Housing Society, 1961.

(12) Hong Kong Housing Society Annual Report 1959, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Housing Society, 1959.